Small government righties: not so crazy after all.

Listen to the broadcast of You Tell Me on KTBB AM 600, Friday, May 17, 2013.

MP3 Download

The calligrapher who penned the Constitution inscribed the words, “We the People,” in script many times larger than the surrounding text. This was no accident. It was intended to visually represent the relationship between government and its citizens, with the citizens standing superior.

Someone at some level yet-to-be-determined at the Internal Revenue Service either forgot or never knew this bit of history. So here is a thumbnail.

At the time the Constitution was adopted, citizen superiority over the government was not a new idea but it was rather new in actual practice. Our constitution traces its roots to the Magna Carta, forced upon King John of England in 1215. That document for the first time sought to limit the arbitrary exercise of power by the monarch. It was only minimally successful in doing so and it would take several more centuries for the idea of citizen self rule to truly take hold.

By 1787, having fought a bloody rebellion against the excesses of King George III, the founders of the United States were quite aware that unchecked power leads inevitably to unchecked abuse. Thomas Jefferson, one of the principal architects of the Constitution, is eminently quotable on this subject. He said,

Even under the best forms of government, those entrusted with power have, in time, and by slow operations, perverted it into tyranny.”

All of this to say that fear and distrust of government are embodied in the very founding of the nation. The arguments at the constitutional convention in Philadelphia in 1787 were at many times bitter and contentious. Almost all of those arguments centered on the conflict inherent in giving government power sufficient to be effective without giving power sufficient to become oppressive.

Two years later in 1789, when the 1st Congress of the United States met, there was strong belief among the constituencies of many members that such delicate balance had not yet been properly struck and that the power of the federal government was not yet sufficiently limited. From that conviction there emerged 12 proposed amendments to the Constitution. Eleven of those amendments would go on to be ratified, ten of which took their place in the document we now call the Bill of Rights.

Legislative, regulatory and judicial overreach in the 20th and early 21st centuries notwithstanding, the U.S. Constitution’s limits on government have been so successful in our 224 year history that it is now fashionable in some quarters to imagine that government need no longer be feared. As a result, talk of constitutional limits and warnings of the dangers of big government are now routinely dismissed by many on the left as reactionary right wing paranoia. For some time now, that characterization has appeared to be winning the day.

Then, as so often happens, events intervened.

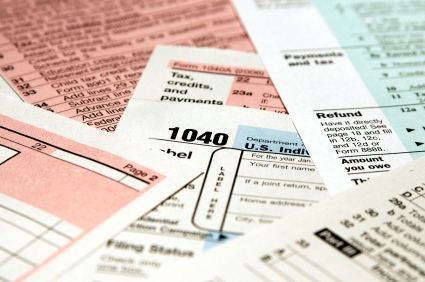

In the past week we have learned that for several years the Internal Revenue Service has been using its fearsome powers as a means to harass, intimidate and thwart individuals and groups who espouse views in opposition to the current administration. In an instant, so-called right wing paranoia has been validated. Conservatives have been handed a clear and easily understood object lesson in support of the principle that as government grows, so grows the likelihood that it will spin out of control and eventually turn on its own citizens.

From this day forward, ‘IRS scandal’ will be useful shorthand for conservatives making their arguments against an ever-expanding government.

Again quoting Jefferson,

The natural progress of things is for liberty to yield and government to gain ground.”

To that timeless quote I would add this corollary: The government that is big enough to give you everything you need is big enough to take from you everything you have, including the freedom to think and speak as you please.

Call that belief paranoia if you will, it is nonetheless not a clinical disorder. It is a condition precedent to the preservation of a free society.

As a clinician, I have had to distinguish many times ‘paranoia from reality’.

Thus the client has to 1st find out what the definition of ‘Reality” is.

Then you apply that to the question at hand & act accordingly.

Politics is harder because emotion clouds the mind.

But still one can define reality.

The hard part is to act on it when your mind screams to disregard the facts.

Watch.

This situation will resolve right back to where it was 2 months ago.

The mind can convince you without you seeing.

Such is ‘MAN’

It takes courage to ‘see’ the truth, but strength of character to change.

Change is very hard.

Very.

I am shocked, Mr. Gleiser, that you of all people would compose and post such a scurrilous attack on conservative character. Throughout our nation’s history, our government has had no more staunch ally that the American conservative.

Por ejemple: (Spanish for “for example” Learn it or be left behind)

When, in the eighties, an American president in the throes of advancing dementia provided weapons to the Ayatollah Khomeini, Saddam Hussein, and Osama Bin Laden your trust never wavered.

When another president years later sacrificed thousands of American servicemen and women while tilting at windmills of mass destruction, conservative support held steadfast and true.

When that same president somehow determined that the fourth amendment did not apply to him and ordered warrantless wire tapping of American citizens, conservatives stood as one and shouted, “Hang the Constitution! We trust our government!”

The list is endless, the evidence irrefutable. When it comes to blind, mindless loyalty to elected officials, nobody can hold a candle to the American conservative.